Behind the Design

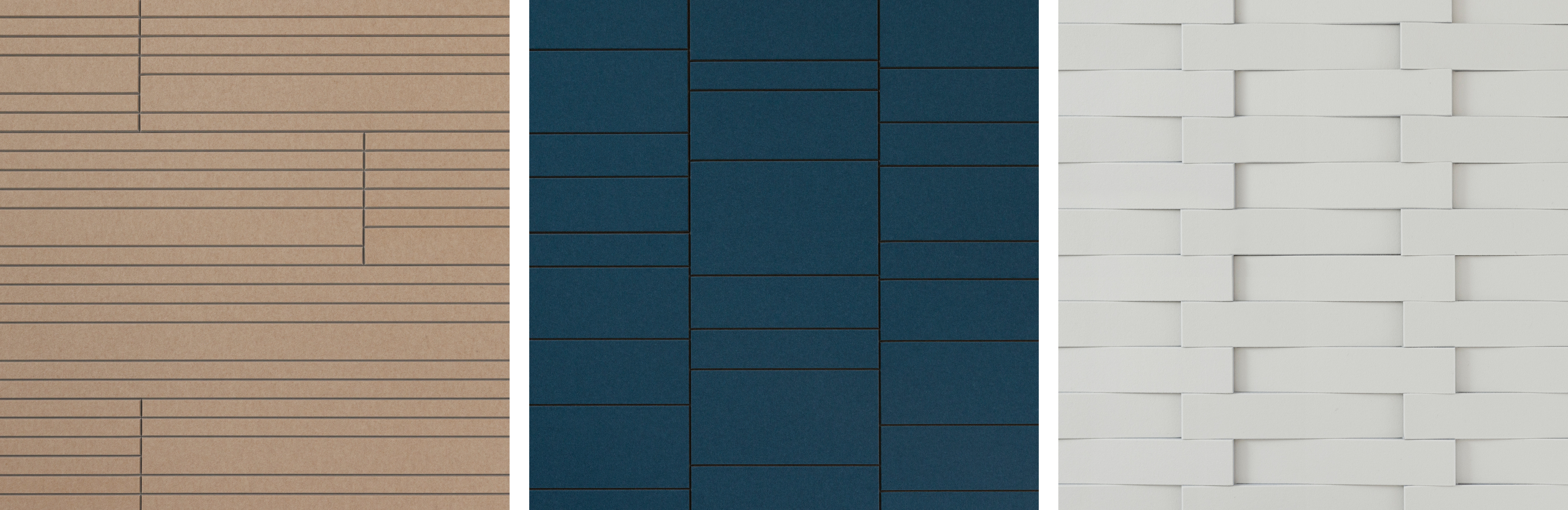

Crossover, Facade, Gap

Bernd Benninghoff grew up surrounded by nature in the Black Forest, in the south of Germany. During his limited free time, you can find Bernd exploring the surrounding areas of his current home in the city of Mainz by foot, bike, skis, and even kayak.

When the pandemic hit and paralyzed most aspects of life this past year, Bernd saw the new restrictions as a rare and unique opportunity to pursue a project that combined his passion for design with his love for the outdoors. So he bought a van and converted it into a small camper in his workshop, and set off to find reprieve in nature.

It was out on the road that inspiration struck for what would become a new collection of wallcovering designs. Driving city-to-city along the base of the Swiss Alps, Bernd naturally took notice of the architecture in each town he explored. Particularly struck by the complexities and patterning of the facades and exteriors that crossed his path, it occurred to him that the same attention to pattern and structure is often overlooked when designing the interior. So Bernd came back to his studio and started conceiving a line of wallcoverings that would bring the outside in.

This past year has been challenging to say the least, in just about every industry. Can you tell us a little about the pandemic's impacts on your life, career, and design process?

Growing up in the Black Forest, in the south of Germany, I was very close to nature. Whenever my schedule allows it, I’m out and about on foot, by bike, on skis, or in a kayak. I also take time out for longer trips—sometimes alone, sometimes with my family. This is the perfect balance to my job as a designer and teacher at the university. At the same time, it’s always a source of new inspiration and ideas.

Last year, when the pandemic brought so much to a stop, I combined my two passions in one project. I bought a bare van and converted it into a small, compact camper in my workshop. The hands-on work was a welcome change to all the online meetings and Zoom conferences. It was important to me that the van’s interior had a clear design aesthetic. Further, it was important that the van survive long trips and still possess a cozy and inviting atmosphere. So far this year, the “tiny house on wheels” has already been used several times for short trips and longer journeys through Europe and has grown close to our hearts.

Despite the challenges that came this past year, some amazing concepts emerged from your studio! What was the inspiration for Crossover, Facade, and Gap specifically?

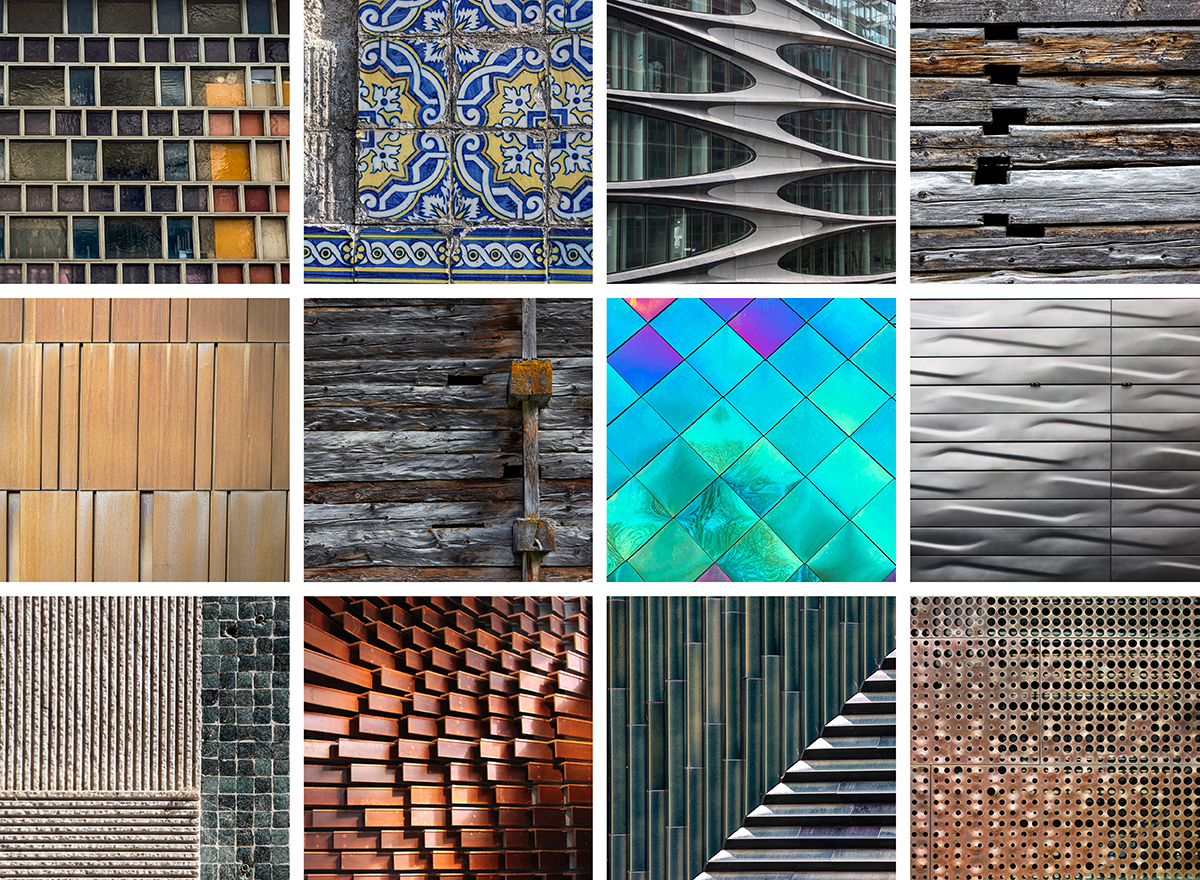

Whenever I’m on the road, I pay special attention to the architecture around me, particularly the structures, colors, and patterns of the facades I pass. The variety of formal and technical solutions and their materials is fascinating and, on closer inspection, often holds surprising depth and beauty. In addition, facades can provide insight into the cultural background, construction period, and formal language of the respective designer. In recent years, my travels through Europe have produced numerous photographs of fascinating building details and structures. These photos have been my source of inspiration for the latest FilzFelt designs.

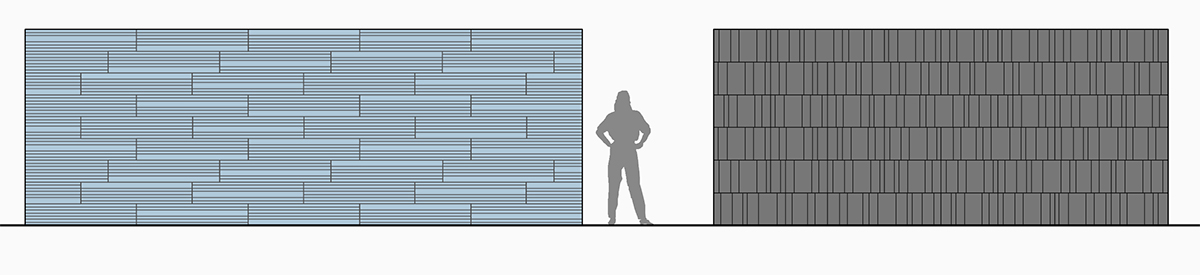

I often cross paths with buildings that are intricately designed on the outside, only to be rather mundane and monochromatic on the inside. With Crossover, Facade, and Gap, I was interested in transferring textures, lines, and three-dimensional depth from the outside of these buildings, to the inside.

“I often cross paths with buildings that are intricately designed on the outside, only to be rather mundane and monochromatic on the inside. With Crossover, Facade, and Gap, I was interested in transferring textures, lines, and three-dimensional depth from the outside of these buildings, to the inside.”

With Crossover, the interlocking design creates depth and three-dimensional patterning. Where did this idea originate?

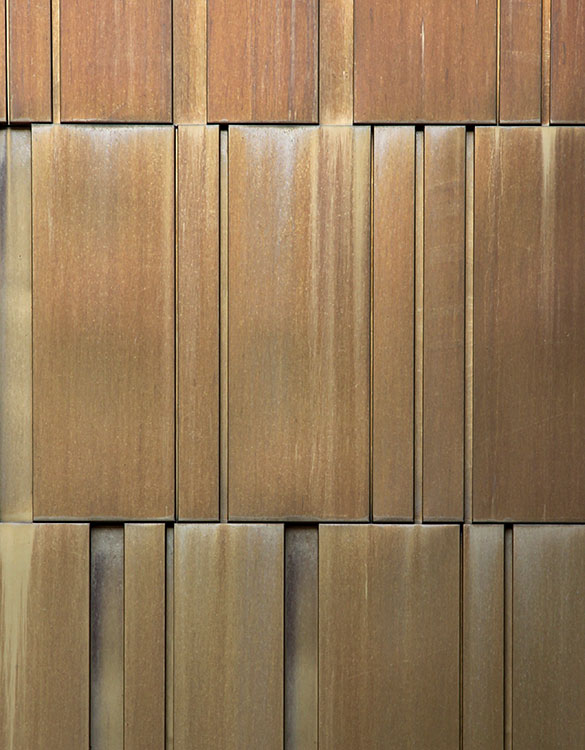

Crossover originated on a hike in the Swiss Alps—in a small mountain village in Valais. Between ancient wooden huts, I discovered a house with a layered and seemingly woven wooden facade—a modern interpretation of the traditional construction method. The three-dimensionality and shadow effect of the wooden exterior instantly fascinated me. I circled the building several times and took quite a few photos.

Back in my office, I started thinking about how to construct this exciting structure— something that could potentially translate for interiors as well. During the process, I strived to develop a concept that would enable the production of interlocking and repeating modules that could easily build out and be added to. This resulted in a whole series of prototypes that were optimized and refined step by step.

The beauty of Crossover is that it can be oriented both horizontally and vertically, giving interiors a very different effect.

Perhaps one day, the interior walls of the Swiss house will be covered with Crossover. Maybe I’ll pack a few modules in my backpack on the next mountain trip.

“I discovered a house with a layered, seemingly woven wooden facade—a modern interpretation of the traditional construction method. The three-dimensionality and shadow effect of the wooden exterior instantly fascinated me.”

Your designs continue to take the efficiency of process and material in mind. How has your process of creating prototypes and architectural products evolved throughout your career?

Experimentation, trial and error, and using models and prototypes take on an increasingly strong focus in my design process. With the help of digital renderings, it’s possible to envision highly complex geometries and shapes.

These can often be incredibly intriguing on their face. Still, it’s not always clear what the manufacturing process will look like or if it can translate successfully during the physical prototyping phase. Over the years, I have learned that products can only function successfully in the market if the design process also directly incorporates the requirements of serial manufacturing.

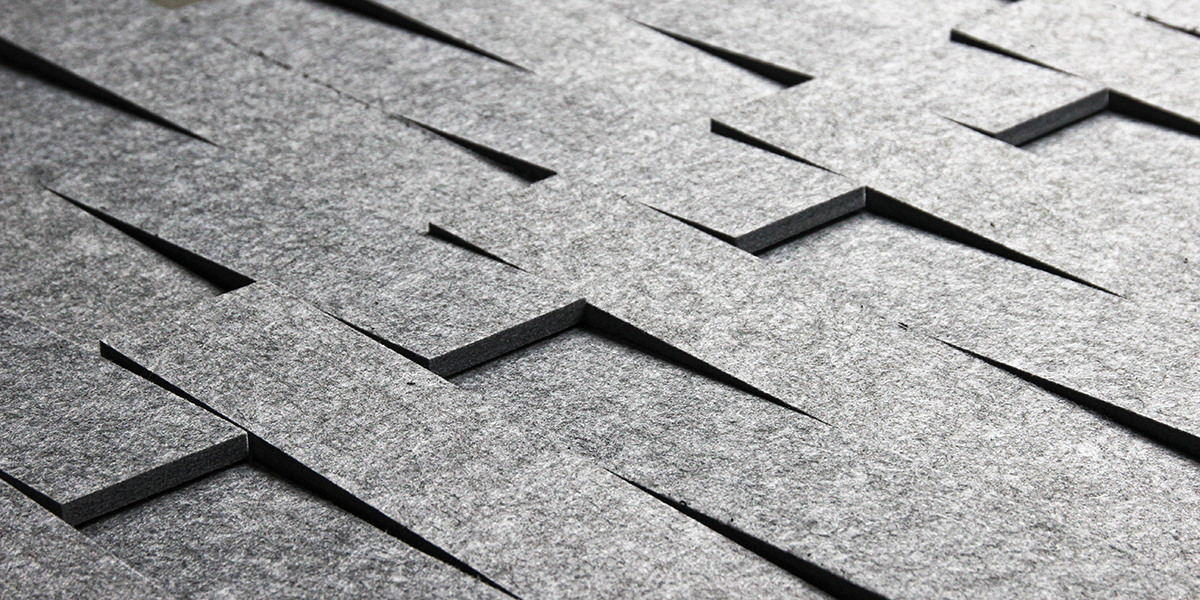

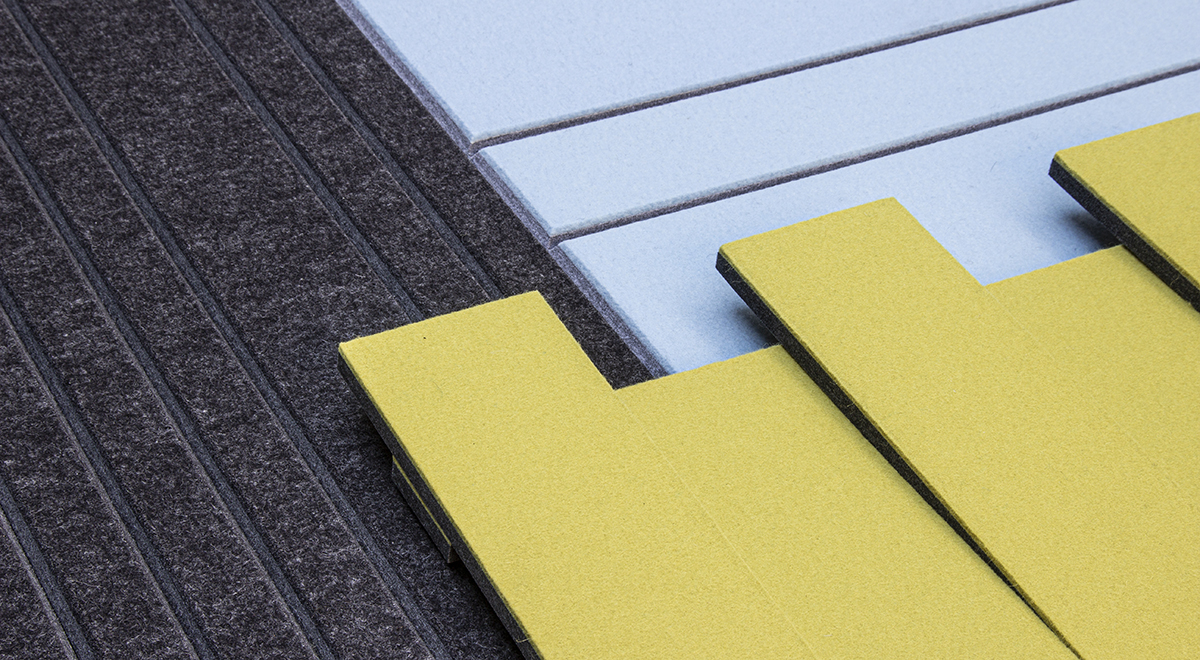

It’s important for my process to always test things by hand to start, to get a feel for the material and details. In the case of Crossover, Facade, and Gap, we built several prototypes to assess the depth and shape of the v-cut detailing. The width and depth of the cuts play a crucial role in the visual impact of the modules for each. In the end, we arrived at the strongest designs through a series of preliminary models.

“With the help of digital renderings, it’s possible to envision highly complex geometries and shapes. These can often be incredibly intriguing on their face. Still, it’s not always clear what the manufacturing process will look like or if it can translate successfully during the physical prototyping phase.”

Despite the issues we’ve faced, what positive effects have the past year had on your work? Do you feel there have been any of note on the design industry at large?

I feel a new and more thoughtful process has begun for so many. The pandemic has shown us that we can get by with less and should value the things that surround us more. Climate change has also become more and more an issue in our everyday lives—we’re needing to be more conscious about how we use our resources.

In recent years, the design industry has launched new products into the market at great speed. Sometimes there was not enough time to plan the products in a sustainable and qualitative way. Good products need time—in both development and manufacturing, as well as in distribution. I hope that this awareness has grown again and that quality and longevity will once again take precedence over quantity in the future. We, unfortunately, have no other choice but to consider every step of the process.

About Bernd Benninghoff

Bernd Benninghoff works as a furniture designer and interior architect based in Mainz, Germany. Since 2000, his design studio has developed serial furniture as well as room and exhibition concepts for international clients. For Bernd, objects and spatial context are interrelated. It is important for him to use authentic materials and appropriate manufacturing processes—in search of meaningful design solutions and room experiences with an independent character.