Happy Birthday,

Eva Zeisel

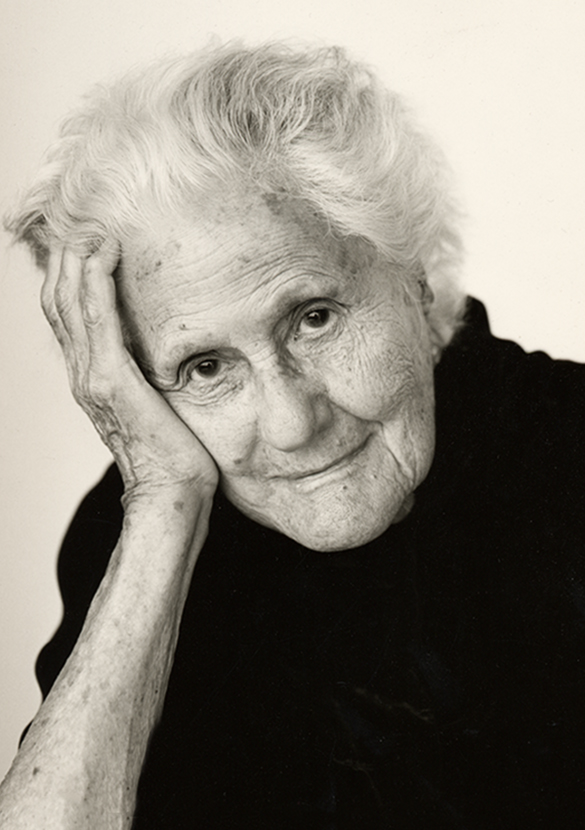

Eva Zeisel is considered one of the most influential industrial designers of the twentieth century, with a career that spanned nine decades. Over the course of her career, Eva designed thousands of pieces that have found homes in the permanent collections of museums worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum, Brooklyn Museum, Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, and The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

She spent the early years of her career in Germany developing the curvy and biomorphic ceramics that would later define her career. At twenty-six, Eva moved to Soviet Russia and became an artistic director in the government’s china and glass industry. In 1936 however, her life took a sudden turn when she was arrested on false charges of conspiring to assassinate Stalin.

For sixteen months, Eva was held in prison, most of which she spent in solitary confinement. After her release, Eva returned home to Austria for a brief time before fleeing to England, and ultimately the U.S. during Europe’s Nazi invasion.

Eva and her husband immigrated to New York, where she established herself as a teacher at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and a ceramics designer with companies such as Bay Ridge Specialty Company, Red Wing Pottery, and Sears & Roebuck. In 1942, she was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art and Castleton China to design a collection to be exhibited in the museum’s first-ever one-woman show.

This year, on what would have been Eva’s one hundred fifteenth birthday, we sat down with her daughter, Jean Richards, to learn more about the significant events, influences, and people that shaped her life and career.

After learning more about her and reading her memoirs in particular, I think it's safe to say that Eva was an incredibly resilient woman. Can you tell us a bit about the kind of woman she was outside of the art world?

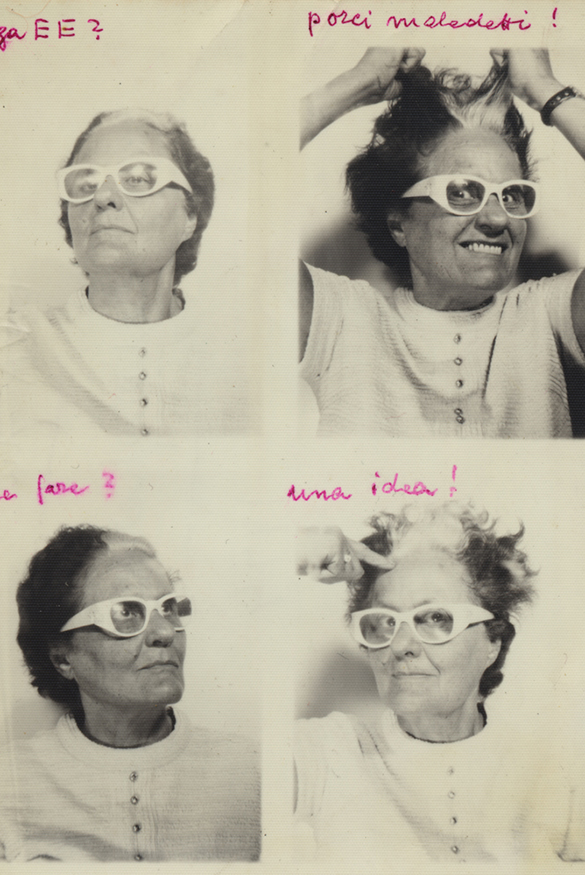

I would say that Eva had a good sense of humor, and was optimistic, adventurous, warm, and playful in her work. But mainly, she was curious. Curious about other cultures, other people.

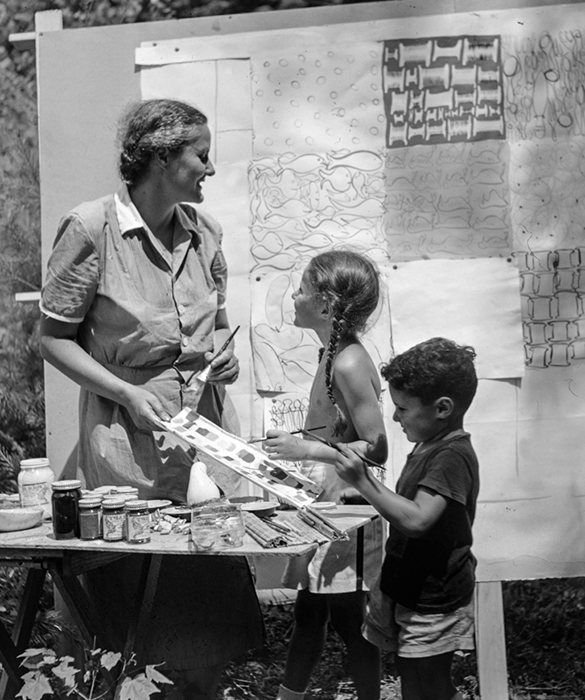

Growing up with Eva was fun. We were always welcome in her elegant, modern basement studio on Riverside Drive in NYC. There was an intercom between the studio and our fifth-floor apartment so that she could keep in touch with the goings-on upstairs. She would joke that when my brother, John, was little, he called her on the intercom in the middle of a business meeting, saying, “Billy kicked me. Should I kick him back?” The yearly Christmas and Easter arts and crafts parties she gave for our whole class in the studio were particularly memorable.

Eva loved to cook, known for her imaginative soups, but she hated housework, considering it a waste of valuable time. Our home life was, to say the least, not rigid. Eva was a warm, imaginative mother. Instead of children’s books, she read us carefully chosen (age-appropriate) short stories by O’Henry and Checkov. She also instituted the ritual of the ‘Tumbalone.’ This was a private, quiet Time Alone with her, for both my brother and me before we went to sleep. We could talk about anything at all.

Eva was once asked how she was bringing up her children. She answered in a letter, “One doesn’t bring up children. One gives birth to them, is good to them, and tolerant, and enjoys interacting with them as one would with others.” I want to emphasize that Eva had a wonderful backup, her mother, who lived next door, and who took care of us, particularly when Eva visited factories.

“Eva had a good sense of humor, was optimistic, adventurous, warm, and playful in her

work. But, mainly, she was curious. Curious about other cultures,

other people.”

Eva’s mother, your grandmother, Laura, was described as a progressive feminist. Your great-grandmother, Cecile was described as “a cigarette-smoking bohemian with radical views who seemingly was not afraid of anything or anyone.” It seems that Eva (and you) come from a long line of strong women.

In 1905, her mother, Laura, was giving lectures in Budapest advocating equal pay for women, etc. she was certainly an early feminist and a peace advocate and historian. She was among the first women to get a Ph.D. at the university. She was also known as a great beauty.

Eva started painting when she was very young but switched gears to apprentice under the last pottery master in the medieval guild system and was, in fact, the first female journeyman.

Eva intended to be a painter, but looking for a way to support herself, became an apprentice to the last master potter of the Hungarian Guild of Chimney Sweeps, Oven Makers, Roof Tilers, Well Diggers, and Potters. There she learned about clay from the bottom up, starting with choosing clay from the mountains, mushing it with her feet, throwing pieces on the wheel, firing them, and selling them in the marketplace. She graduated as a journeyman and put an ad in the journal saying she was a fully trained journeyman, and that is how she got her first job in Hamburg.

“She learned about clay from the bottom up, starting with choosing clay from the mountains, mushing

it with her feet, throwing pieces on the wheel, firing them, and selling them

in the marketplace.”

In her memoirs, Eva references several poems she wrote during her experience in prison. I imagine it was the only form of art or expression afforded her during those months she was incarcerated. And she continued to write long after her release. When did she start writing poetry?

She would write little songs and poems for us when we were little, mostly educational. The one that I never forget is called ‘Life.’ She wrote it to me when I turned ten. “Now that you are old enough, I thought that you might want to start to figure out how to live right, but how can you if you don’t know precisely where and when life is? So, I wrote this poem for your birthday.”

The poems Eva wrote and recited in prison were extraordinary. They were composed in German. Her prison cell was six steps diagonally from corner to corner, so she incorporated that meter into her poems. Apart from poems for her children, she did not continue writing poetry after her release.

She often mentions that she would practice mental exercises during her time there so that she wouldn’t lose hope. And like you said, she had those six steps across her cell to which she would write poetry. It seems she had a few rituals to keep her sanity, poetry certainly being one of them.

She had several ways of coping with her sixteen months of prison life. Besides writing poetry, she did exercises, often standing on her head. To keep her mind busy, she played tic tac toe with herself, using small pinches of bread. Once, she used the time well to design and construct a brassiere (in her head). Occasionally she had cellmates, kind folks from whom she learned a lot. Her Russian was good. They were allowed some books, as well, but mostly they fantasized about food.

She also had a peculiar ability to see herself, the absurdity of her situation, from the outside. She told me that she traveled through life as a tourist. Most of the time, she managed to keep her dignity and equanimity in prison. And I think that’s very important. She was a tourist even in her own life. And seeing herself from the outside, I think, helped her tremendously in that situation.

She spent 16 months in prison. She spent time in solitary confinement. She described every day as presumably her last. She even describes the experience of attempting to end her own life. After she was released, there was a period of time you described her as “completely kaput.”

Totally kaput. In fact, on the train going out, she described a conversation she had with a man, a stranger. When she was asked how old she was, she said something to the effect, “What do you think?” And, he said, “Not a day over fifty.” And, of course, she was only thirty. So, when she got to Vienna, she had no will. She had no strength. She had nothing. She was totally shut down. It was several months that she was just couldn’t function.

An experience like that could leave you in that darkness for the rest of your life, or at the very least, you’d likely suffer a form of post-traumatic stress. So how did she find her way out of that? Was she able to use art and design as a form of healing?

It wasn’t immediate, but some time during those first six months in Vienna, she made a contract with a Hungarian factory she was going to work with. Still, it never came to anything because on the day Hitler marched into Vienna, March 12, 1938, Eva took the last train out of Austria. “I could not stand another trauma,” she said later.

Of her ceramic collections, you’ve said that “she always designed in relationships, never a piece by itself. She said the pieces all had to be cousins.” A stark contrast to the experience of spending months in solitary confinement. What was the significance of designing pieces meant to work together and never on their own? Why was this so important to her approach to design?

She said that the pieces in a set did not have to be siblings, but they should be cousins. I’m not sure why she designed in relationships, but some of her designs were inspired by human forms (belly buttons crop up in many of her designs). A museum curator once referred to another of Eva’s inspirations: baby’s bottoms!

Her salt and pepper shakers for RedWing were meant to be mother and child, based on her and me. But I am quite sure that her isolation in prison did not affect her designs. They did affect her attitude toward life, however. She said that she felt that her life after prison was a gift, as she had so nearly lost it.

Birds make an appearance in many of Eva’s designs. In her ceramics, many of the painted details, and later in her furniture design, she incorporated them often. What inspired this continuous reference?

In Hungary, birds are very popular in folk literature. And I once came across a quote from her, which says, “When you put your hands in clay, it’s very hard not to make a bird.” So, the birds from her work and designs come from the Hungarian folk tradition.

“In Hungary, where she came from, birds are a

popular theme in folk art. I once came across a

funny quote from her, ‘When you put your hands

in clay, it’s very hard not to

make a bird.’”

There seems to be a significant relationship between form and function in her work. You’ve said, “She always designed her pieces as a gift for others, for the user. She didn’t believe in self-expression.”

Regarding function, she said, “Of course, an object has to function. A teapot has to pour correctly, etc. That is obvious. But within that function, there is an infinite number of esthetic choices, and that’s where design comes in.”

Regarding Eva’s design as a gift to the user, that was absolutely true. She was proud that her fan mail often included the word “love,” as in “I love that bowl.” The fact is that she put love into her designs and was glad when that love was communicated to the user.

In this regard, it makes sense that her work would be a good fit and translate so beautifully into wall tiles for FilzFelt. These are architectural products with a very clear function and purpose. Most commonly, these are intended to perform acoustically, so there is that direct function, but you combine it with her design, and therein lies that perfect relationship between form and function.

Yes, and on that, some of those patterns were originally actual clay tiles which also had a function. I would say that everything she designed, except her early paintings, everything she designed had a function. She never designed an object that was simply pretty to stand or display. I mean, there were a couple of things she designed that were just silly. I remember a little wooden lady with bells, and you could move her back and forth, and the bells would ring. That was simply fun. But really, anything she designed had a function, either tiles or acoustic tiles, or cups, and even her space dividers had a function, which specifically inspired the FilzFelt tiles. The belly button that inspired the FilzFelt tile (Spindle Block) was originally a three-dimensional clay tile, that went on rods to make a transparent wall. So those shapes had three functions. One was a three-dimensional tile, one was a flat tile, and one was an acoustic tile. So, in everything she did, the design had a function of some sort.

I know if Eva were still alive she would have a huge amount of fun playing with the FilzFelt tiles and putting them together in different ways. She would have been thrilled that her beloved shapes made in gorgeous colors by FilzFelt have a brand new function (and she probably would have put them up on all her walls!)

Her influence in the art world is significant. Her work crosses so many disciplines, generations, and industries. Her work, it seems, holds the resilience and timelessness that she did in life.

Yes, at one point, a while back, she was at an event at the 92nd Street Y with the designer Jonathan Adler. And it was the very old and the young in a discussion. So this was Eva. And this was Jonathan. Eva was ninety, and Jonathan was twenty-five. And, even more recently, I was called by the head of design at Nike. Amazingly, he had all his designers study her work.

It’s Life you are living and life is here.

It’s not sometime later, it’s now, Jeannie dear.

It’s not a road with beginning and end.

It leads not anywhere, it’s the time you spend.

It’s life when the sun shines, it’s life when it rains,

not where you are going, but riding the trains.

Life is not a stamp collection of memories of the past.

Life is in the present tense, the memory while it lasts.

The cloud that hurries gently by, the bunnies’ funny leaps,

if you hug them with your eye, belong to you for keeps.

Don’t think that once will come a day when we’ll all be rich and smart

and laughter will be here to stay, and then real life will start.

Between the not yet gilded past and the time for which we strive lies,

unnoticed and not to last, the moment which is life.

"Life", by Eva Zeisel (1950)

.jpg)

Though best known for her modernist ceramics, the Eva Zeisel Collection for FilzFelt takes inspiration from her room dividers and glazed tiles in six shapes of acoustic tiles that feature curvilinear forms nesting together to create soft, fluid patterning. In true Eva Zeisel spirit, the playful patterns may go bold with saturated colors or soft and sensual with neutral tones